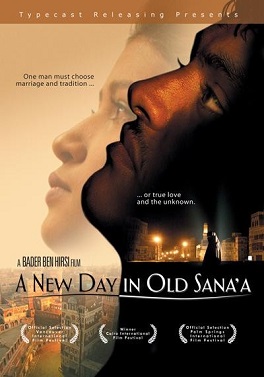

When speaking on stereotypical Arab representations in Western media, nothing shows the disparity between Hollywood and Arab cinema much like the juxtaposition of the war film Rules of Engagement (2000) and the Shakespearean drama A New Day in Old Sana’a (2005). Rules of Engagement fails to display conflict in the Middle East rationally and uses blatant stereotypes of Yemeni civilians as crazed terrorists who were brainwashed by Islamic doctrine. In contrast, A New Day in Old Sana’a addresses the problems of classism and religious oppression while still giving dignity to the Arab characters who are shown to have actual feelings and motives that ground them and make them relatable.

Ironically, Rules of Engagement is the doctrine of the Military Industrial complex that is spread throughout this propagandistic film that brings the most terror, rather than the radical Islam it likes to demonize. It is especially telling in this story that Islamic terrorism and extremism is looked at “as a symptom of the Otherness of the Arab world, rather than as a problem within it” (Khatib 166). Much more likely to cause radicalization is the bombing of innocent civilians carried out in the multiple Middle Eastern wars of the United States. Rules of Engagement ignores all context of the history of imperialism and colonialism in the Arab world and that is why it fails to do much else than serve as a propagandistic tool that dehumanizes Arabs in order to justify a perpetual War on Terror. This aforementioned propaganda must have helped sway public opinion in some way as little is said today in opposition to the Saudi led, American funded genocidal war leading to severe starvation and disease in Yemen today. In fact, Rules of Engagements justifications for slaughter have been mirrored in the recent ramping up of war and violence by the Trump administration as the “US carried out 37 drone attacks in Yemen in 2016… but by October, the US had carried out 105 drone attacks in 2017” (al-Mekhlafi 5).

Interestingly enough, the “original – entirely fictional – story, written by James Webb, secretary of the US Navy in the Reagan administration, placed the events in an unnamed Latin American country” (Whitaker 2). This shows how the scapegoat for American imperialism can come from any source and is not limited to simply targeting Arab stereotypes. However, once US interest veered from establishing Banana Republics and toppling democratically elected leaders in Latin America to controlling the petrodollar in the Middle East; the target of discrimination was appropriately changed.

A New Day in Old Sana’a battles the stereotypes specifically leveled at Yemeni civilians by showing the true Arab world as it “is not, as is often perceived, a monolith, but is made of different communities, people, states, and governmental and societal forms” (Shafik 1). The love story between Tarek and Bilquis in the film brings the audience to care for the characters and not see t hem all as simply enemy targets. A strong plot that does not even focus on war does more help to show these diverse humanizing features, as well as the well-timed comedy that allows for the audience to relate and see them as fellow people and not an othering force. For example, Bilquis’ openness and freedom to try on the dress and dance in the street at dawn goes against all preconceived notions of conservatively repressed Arabs and Muslims that is believed to have universally and monotonously controlled even the youth of the Middle East. It also does well to still address questions of classism and religious extremism but in a tactful and respectful manner that is much more intellectually engaging than the violence-drenched gore fest seen before.

hem all as simply enemy targets. A strong plot that does not even focus on war does more help to show these diverse humanizing features, as well as the well-timed comedy that allows for the audience to relate and see them as fellow people and not an othering force. For example, Bilquis’ openness and freedom to try on the dress and dance in the street at dawn goes against all preconceived notions of conservatively repressed Arabs and Muslims that is believed to have universally and monotonously controlled even the youth of the Middle East. It also does well to still address questions of classism and religious extremism but in a tactful and respectful manner that is much more intellectually engaging than the violence-drenched gore fest seen before.

Films from the Arab world, such as A New Day in Old Sana’a, can help fight propagandistic representations from Rules of Engagement and other Hollywood films that only serve to dilute our view of the true situation and promote a militaristic ideology. They do this by showing the actual societies that are being portrayed as they are familiar with them and can do them justice. They still address the problems that face their society but are not blind to the historical context of imperialism that wraps the Middle East in turmoil today. Rules of Engagement irresponsibly ignores this historical context and prefers to use unfounded stereotypes to push its agenda.

Word Count: 722

Works Cited

al-Mekhlafi, Mohammad. “World Report 2018: Yemen.” HRW, Human Rights Watch, 2017. Web. 20 Apr. 2018.

Friedkin, William, Dir. Rules of Engagement. Perf. Samuel L. Jackson & Tommy Lee Jones, Scott Rudin Productions, 2000. Film.

Hersi, Bader Ben, Dir. A New Day in Old Sana’a. Perf. Dania Hammoud & Nabil Saber, Felix Films Entertainment Limited, 2005. Film.

Khatib, Lina. Filming the Modern Middle East: Politics in the Cinemas of Hollywood and the Arab World. London & NYC: I.B. Tauris, 2006. Print

Shafik, Viola. Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity. Cairo: A.U.C. Press, 2007. Print.

Whitaker, Brian. “The ‘Towel-Heads’ Take on Hollywood: Arabs Accuse US Filmmakers of Racism over Blockbuster.” The Guardian, The Guardian, 11 Aug. 2000. Web. 28 Apr. 2018.