Tanvi Marulendra

The Nights of the Jackal (1988) chronicles the breakdown of a rural, Syrian family. In doing so, it presents a subtle criticism of the patriarchal system that dominates Syrian families and (with the government acting as a controlling father-figure) the country as a whole. The most prominent example of this subtle political criticism in the film The Nights of the Jackal is seen through the portrayal of the father, Abu Kamel, as a belligerent incompetent, and the mother, Umm Kamel, as a peaceful problem solver and coexistent. Abu Kamel is representative of the current Syrian regime, in desperate need of a change in attitude, while Umm Kamel shows the director’s ideal version of the state; the type of person that Abu Kamel (and by proxy, the Syrian government) should be, and must become if he (and Syria) is to protect his family (the nation).

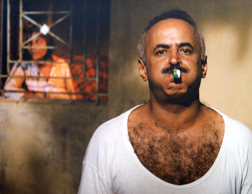

One major, recurring instance of these characterizations of Abu Kamel and Umm Kamel as dysfunctional and effective respectively is the problem of a pack of jackals that return every night to howl at the family. Abu Kamel must rely on his wife to whistle at the jackals, which drives them off every night without fail, and allows the family to rest peacefully. On his own, Abu Kamel has no way of driving off the jackals; when he cannot teach himself how to whistle he buys a cheap, plastic whistle. The jackals are not fooled by this insincere gesture, they continue howling until Umm Kamel makes a genuine outreach with her usual whistle (Abdelhamid).

Abu Kamel attempting to scare the Jackals with a whistle.

This scene takes on a much weightier significance when the symbolism behind each of the characters is taken into account. Khatib, a well-known analyst of Middle Eastern Cinema, describes women as, “the moral gauge in society” and “the bearer of the nation’s values” (Khatib 80). Umm Kamel is patient, hardworking, willing to reach out to her enemies (the jackals) without jumping to aggression; she is essentially a representation of the ideal form of the nation. In contrast, Abu Kamel is belligerent and quick-to-anger. He rarely tries to reach out to the jackals, and when he does it is with an empty, cheap, ineffective gesture. In a similar way, the Assad regime in Syria (which took power in 1970) has demonstrated an affinity for violent acts and dictatorial control over its citizens. These tendencies were put on display several times in the past decades, through the attempted subjugation of opposition groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood and Free Syrian Army (Holliday). Thus, Abu Kamel is representative of the violent regime controlling Syria, just as he uses force to control Umm Kamel and the rest of the family.

It is likely that if Abdellatif Abdelhamid, the director of Nights of the Jackal, had outright criticized the Syrian government, the film would have been banned from distribution or severely censored (Wedeen 105). Instead, by putting in Abu Kamel as a stand-in for patriarchal systems, specifically that of the Assad regime, he could criticize their true nature, while still ensuring the film’s circulation in Syrian cinemas. Abdhelamid’s criticism is revealed in his characterization of Abu Kamel, which is largely done through the character’s actions. It is fairly traditional that as the head of the family the father is obeyed with little question (Tanford 1), however Abu Kamel takes his power to unnecessary levels and allows his anger to dictate his actions. When his children do not satisfy his expectations he beats them and shouts, with little to no damper on his aggression. In one comical scene the family prepares to go out to the fields where they grow tomatoes; Abu Kamel climbs onto a tiny donkey and is handed his lunch and tools. The laden-down donkey sets off with Abu Kamel on its back, and the rest of the family follows, equally burdened the rest of the family follows on foot with additional materials and equipment (Abdelhamid). When they finally reach the field the whole family works, including the youngest son, until Abu Kamel injures his foot and collapses dramatically, accusing Umm Kamel for his own mistake, and refusing to continue working (Tanford 1). It exposes the hypocrisy of the regime that the patriarchal figure, who is typically the provider for the family, is so eager to laze out of work, and then blame others for his wrongdoings. Once the tomatoes are finally grown and harvested Abu Kamel finds out that the price of tomatoes has dropped drastically; in a fit of rage he stomps through the ripe crop, mashing them into a worthless paste. Thus, his (and by extension, the regime’s) lack of consideration for the people’s hard work is revealed.

Clip of Abu Kamel Smashing the Tomatoes (CinemaSyria).

Through the extended analogy of Abu Kamel as the Assad regime, incapable of peaceful coexistence, dictatorial, and selfish, Abdelhamid was able to criticize the Syrian government safely. At the same time, he contrasts Abu Kamel with his wife, who represents the ideal nation that Abdelhamid believes Syrians should strive for, peaceful, willing to reach out to and negotiate with enemies, and hardworking.

Works Cited

Abdelhamid, Abdellatif, director. The Nights of the Jackal. General Organization Cinema, 1988.

CinemaSyria. “ليالي ابن آوى.” Youtube, 8 May 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8jZzE46whUw

Holliday, Joseph. The Assad Regime: From Counterinsurgency To Civil War. Institute for the Study of War, http://www.understandingwar.org/report/assad-regime.

Khatib, Lina. Filming the Modern Middle East : Politics in the Cinemas of Hollywood and the Arab World, I.B.Tauris, 2006. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/fsu/detail.action?docID=676857.

Tanford, Eleanor S. “Culture of Syria.” Countries and their Culture, Advameg, 2017. http://www.everyculture.com/Sa-Th/Syria.html

Wedeen, Lisa. “Tolerated Parodies of Politics in Syrian Cinema.” Film in the Middle East and North Africa : creative dissidence, edited by Joseph Gugler, 1st ed., University of Texas Press, 2011, Texas. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/9067711