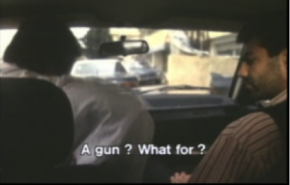

In A New Day in Old Sana’a, Yemen’s first feature length native film, filmmaker Bader Ben Hirsi creates a cinematic masterpiece, which realistically illustrates what love and life are like for young Yemeni men and women. “The representation of human fate on the background of an entire social context forms the essence of the realist genre,” of which Hirsi’s film definitely falls under (Shafik). The story revolves around Tariq, who is betrothed to Bilquis, a very suitable young lady from a wealthy family, whose father is a judge. But despite their social compatibility and Bilquis’s prominent family, Tariq finds himself in love with another woman. However, Ines is not a good match for him at all, due to her low social status as an orphan who makes a living by applying the nagsh (henna designs) to people as a service.

Hirsi’s film serves to illuminate the reality and complexities of love and marriage within the culture of Yemen through the characters of Ines, Tariq and Bilquis. “…such stories really do happen often in Yemen…for people in Yemen it’s an important issue” (Hirsi, interview). Contrary to our Western misconceptions and predispositions about arranged marriages, the process is embraced and respected still by younger generations. It is done with the intention of providing the best and most secure life for the two parties involved. The two families marry into one another-it is not just about the couple themselves, and familial honor is of the utmost importance.

The pressures Tariq faces from his sister ultimately lead him to abandon his feelings and own personal happiness, in favor of respecting his family and the match they have found for him. While he does love Ines very much, selfish feelings are not cause enough for him to abandon his responsibility to honor his family. His sister does not seem to care the least bit about Tariq’s happiness and she chastises him for even considering not marrying Bilquis. In this exchange, it is clear that the idea of breaking a betrothal is not an option for an upstanding man like Tariq. He sacrifices true love, in order to fulfill his duty. He chooses the long-term happiness of everyone else over his own.

For Ines, her deliberation on whether or not to run away with Tariq comes a bit easier. She does not have a family pressuring her to honor them. Because of her social status, she has a little bit more personal freedom. But despite this, she still is extremely hesitant to just run away from her society for true love. She understands and respects the positions that both Tariq and Bilquis are in, and for a long time would not give in to her feelings. She attempts to rebuke Tariq as he speaks to her from the other side of her front door.

“The movie does a fabulous job in portraying how life is in the conservative country of Yemen,” while remaining a realist film in terms of how it depicts love, duty and the complexities of human emotion (Jarjour).

Works Cited

A New Day in Old Sana’a. Dir. Bader Ben Hirsi. Perf. Nabil Saber and Dania Hammoud.

Felix Films Entertainment Limited, 2005. DVD.

“I Wanted to Make a Film Which People Everywhere Would Understand.” Interview by

Larissa Bender. Qantara.de. German Federal Agency for Foreign Cultural

Relations, 31 July 2006. Web.

Jarjour, Maya. “‘A New Day in Old Sana’a’ Highlights Inner Struggle between Family

Honor and Love.” McClatchy – Tribune Business NewsMay 19 ProQuest. Web. 2 Dec.

2015.

Khatib, Lina. Filming the Modern Middle East: Politics in the Cinemas of Hollywood

and the Arab World. London: I.B. Tauris, 2006. 1. Print.

Shafik, Viola. Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity. Cairo, Egypt: American U in

Cairo, 2007. Print.